A call for new ideas on an old theme!

The sad impulse to write this article is two accidents within one week on my home drome, Oerlinghausen. A student declared from a good height that he was ending his flight. He landed very hard and suffered a back injury. The glider was heavily damaged.

An older pilot with 40 years (!) of flying experience returned fairly close to the field but flying very slowly. He stalled at about 100 feet and dove into trees. He died two days later in hospital.

It is discouraging and sometimes I ask myself seriously what I’m doing building gliders. Nevertheless, these accidents have brought me to thinking about a very simple question:

Every simple Cessna and the like have a stall warning system. We have none. Why? More exactly, why do many pilots think a stall warning device is unfashionable and don’t want one?

Everyone knows that among all of the causes of accidents, stalling near the ground is the most common and often ends in death. A complete avoidance of such accidents is, of course, impossible. But the question must be asked, in any case, whether an obligatory stall warning system would drastically reduce their number.

This kind of accident occurs under many different conditions:

Landing, winch launching, aerotowing, in mountains without a good view of a horizon, and after entering bad weather.

This question is not new and I have often discussed it with pilots. I’ve heard many arguments and have learned a lot. In addition, I asked the question on “rec.aviation.soaring” and received a wide range of responses.

In all questions of safety in gliding, a manufacturer must think carefully about the answers. If we were to put stall warning indicators on all of our gliders as standard equipment, pilots would say, The wings from DG are trash. That is seen by the fact that they must put stall warning indicators on all of their ships. Other designs don’t need them. I’ve heard this point of view many times and it brings me to the dark suspicion that this is the reason why manufacturers have not to this day put in stall warning indicators as standard equipment.

Let’s start at the beginning with the aerodynamic root of the problem in flight physics.

An aircraft flying fast has a lower efficiency than a slower flying aircraft. If you want to glide as far as possible from a given height, use the best glide speed which is about 57 knots for a modern glider. If you want to minimize sink then fly at the minimum sink speed of about 44 to 49 knots depending on wing loading. If you reduce the speed even more, by flying at a still higher angle of attack, the flow across the wings will suddenly break up. The drag increases markedly and the thrust due to weight diminishes. One or both wings stall. If only one wing stalls, then the aircraft enters a spin.

A stall warning indicator should give warning at a speed of about 5 to 10% over the stall speed, in order to give the pilot time to push forward on the stick and increase speed before the aircraft becomes uncontrollable. Such a warning should drastically reduce accidents caused by flying too slowly, in normal landings especially outlandings, and also in mountain flying.

What is the situation in gliders?

Why don’t they have stall warning devices?

- One reason is that we don’t want a flap valve on the wing as in airplanes because it disturbs the airflow too much. However, a sailplane manufacturer can drill holes in the nose to take pressure measurements and get a stall warning system of sufficient precision.

- In contrast to airplanes, we often fly very near stall speed in small thermals. In that case the stall warning would be bleating at us constantly. Do we want that?

This argument is the most common one against a stall warning device.

But it is wrong!

I was flying with a DSI several years. It does not beep so often.

It only beeps when you fly extremely slow or – even more – if you suddenly fly a steep curve.

Well, do we want such a warning in these situations?

We should!

When we fly very near stall speed in thermals, we are flying at a high sink rate. It doesn’t make any sense to fly that slowly if our intention is to achieve maximum climb rate in the thermal. The danger of stalling is too great and if another glider is under us, it could lead to an accident. The main thing is that we achieve nothing by flying on the edge of stall.

Modern airfoils with smooth transitions between the wing and fuselage loose performance drastically when nearing stall speed. Older gliders had a softer transition. It’s actually a good thing when the stall warning sounds during thermalling.

We are, in fact, flying too slowly and the warning shouldn’t get on our nerves, rather it should tell us to fly faster or at a shallower bank angle.

- The manufacturers have for decades tried to prevent the construction regulations from being too confining. And the customers (the market) have not as yet demanded a stall warning indicator.

Why not?

I don’t know.

You are the customers!

In the automobile industry there is considerable pressure from the customers for development of crush proof passenger compartments, air bags, and other safety systems. In contrast, for sailplanes there is almost no such market pressure. Why?

At present, only by order of an administrative authority, could the use of stall warning systems be imposed universally because if only one manufacturer offered it……… See above!

- A stall warning system is probably a money saving device.

How many landing gear systems have we had to repair in our club?! With that money we could easily have equipped twice as many gliders with a DSI. I have done considerable damage to the gear in my DG-400 without any good reason, only stupidity. This would have definitely not happened if I had had a stall warning indicator. For the 8,000 Euro I spent on repairs, I could have equipped the whole club fleet with DSIs.

Further arguments:

- “We don’t want any more warning buzzers in the cockpit. The pilot gets confused afterwards as to which beep means what and forgets to put down the gear.”

Well, yes, if one puts the gear down right away, then it doesn’t beep in the first place. And when the stall warning sounds then one should recognize it within the context of the flying situation. In addition, the DSI displays the reason for the alarm.

To be sure, one thing has already happened: a customer programmed his hand-held GPS with his home glider port. In the pattern it beeped with the message, Arrival at Turnpoint. The customer thought that the gear was still up and pulled the lever back – Ow!

We are of the opinion that a legitimate warning should also sound off. And a warning due to under speeding is truly legitimate as you can read from the first sentence of this article. The same is true of a gear warning.

- He, who is not in a position to control his speed, should not get into a glider!

I hardly dare say it but this is a quote from a high official of the German Aeroclub in the instructor’s school. What can you say to such nonsense when even a pilot with 40 years experience crashes? Has he never been in a cockpit? Personally, I have had the exact same experience that I never should have. Never!

Can’t you imagine the following scenario happening to you?

You’re flying along a ridge in the mountains. In spite of the turbulence, the ridge is working well and you’re keeping in close and flying slowly in order to stay in the lift as long as possible. As you pass a gully, you don’t notice anything in particular – because you don’t have a stall warning indicator – but a gust from behind hits you and the ASI takes a dive. At the same time you attempt to turn away from the ridge. It stalls and you plunge toward the ridge……..

I have, myself, already experienced the first part of this scenario. Before I could experience the second part, a loud beep caused me to automatically shove the stick forward.

- I have already written above about the possible conclusion that our airfoils are worthless if we build in a stall warning horn. That is complete nonsense, but what can one do to counter such propaganda? I’ve just come from the glider port where I tried repeatedly with different maneuvers to stall my DG-800 by mistake. I could not succeed!

It might have been possible with an extreme aft C.G. That is not possible through the luck (or sorrow) of my weight. (205 lbs.) But we all know that some gliders are much less tolerant to slow flight.

The mistake-tolerant system

I would like to restate the theme in a broader sense and simply enumerate the ways in which I would imagine myself as a glider customer. (And that is, of course, the way we as manufacturers build gliders.) It makes no difference that the three most important things which increase flight safety are:

1. Training

2. Training

3. and above all, training!

Even so, there are too many accidents in our sport and we, at DG, are convinced that this fact itself imperils the future of our sport. Every accident and especially every fatality discourages another possible joiner from trying our wonderful sport.

Okay. How should our gliders be equipped?

A glider must work like a mistake-tolerant system.

- It must warn me right from the beginning against dumb mistakes which could be avoided if the glider had:

- Stall warning

- Spoiler warning or Piggott Hook

- Speed warning

- Remote control of the glide calculator

- Good visibility from the cockpit.

- To correct or diminish dangerous situations, the glider should have:

- A nose hook for aerotowing

- Harmless airfoil characteristics

- No extreme aft C.G.

- To give more protection in a crash, the glider should come equipped with:

- NOAH system

- Latest safety cockpit technology

- Roeger hook

If we always built such well equipped gliders,

the accident rate would go down.

But only you, the customer, can make it happen!

Maybe it’s only a question of time until there is a change of mind and a warning system is no longer seen as unfashionable, rather a necessity. And maybe this article will help to start a change of opinion.

Why is it always necessary to have a few pilots die until a new round of discussion begins?

It is clear that I, personally, make no friends among my colleagues when I suggest we do what they have for years avoided doing. Even in my own factory I have to convince some people.

Maybe I’m being one-sided about this by putting my own personal opinion above everybody else.

That’s possible.

Simply tell me!

I am mistake-tolerant – even in enduring criticism.

– friedel weber –

The following story is too good not to tell but will be told under cover of anonymity.

A competition pilot, whose name is well known, had to wait a long time for a tow in his DG-800.

1. He didn’t make a second ground check and so missed the fact that his DSI had gone into sleep-mode in the meantime. Thermals didn’t work so he found himself in the pattern pretty soon.

2. He had fooled around long enough that he wound up well into the pattern. In front and above him was another pilot who wanted to land first. This other pilot flew a big pattern so that our pilot had some concern as to whether he was high enough to stay in line.

3. As a result, he cut his base leg short and flew a diagonal to final ahead of the other pilot.

4. As can be expected, he made the only-to-human mistake of forgetting to lower his gear.

The story is only for laughs because the scratches on the pilots self-esteem were deeper than those on his gear doors. Of course, before take-off, he proclaimed that such a mistake would never happen to him……

That is the reason we need mistake-tolerant gliders.

Sometimes such situations don’t go as we have planned but afterward we can just smile about them!

My friend, Jens, is dead!This article was written but not published, when my best friend died in a winch launch accident. He flew behind the cable, gained only 100 m, and then released. He apparently intended to fly a shortened pattern and land. Flying much too slowly in the turn back after release, he stalled and crashed straight in on the field. Jens was no daredevil; he was a highly knowledgeable pilot who was well known for his fussy cockpit checks. He was the only one I allowed to fly my glider from time to time and had suggested many technical improvements. He took care of all the technical devices in the club with exacting attention to detail. Anywhere there was a problem, the cry soon went out, Jens, can you look at this for a moment? It is just terrible!

Born 1947 Died May 7, 2000 |

Maybe I’m getting on the nerves of some of you with my intensive preaching about safety issues. I only need to read the newsgroups to see opinions such as:

“The nose hook ruling for aerotow is idiotic. A stall warning, a gear warning, and a spoiler warning systems are unnecessary. A spring check ride with an instructor is an imputation.” And I have heard many other unreasonable demands. But I have three or more hairy experience behind me, especially during the beginning of my flying.

If I’m irritating your conscience, you can just quit reading here. Jens knew all these articles and it didn’t help him! But what is the use? It’s got me!

My invitation above to more discussion seems meaningless now. In light of this accident, nobody can say that my argument for a mistake-tolerant glider in general, and a stall warning system in particular, is nonsense.

But don’t trouble yourself.

Just keep writing exactly what you think.

– friedel weber – translated by David Noyes, Ohio

Now let the discussion of the theme begin……..

Postings of the Newsgroup before this article was published:

Hello

I fully share your frustration with the continued stall/spin accidents that haunts our beautiful sport, and I think that any well-working stall warning system would indeed be considered “Cool” by the majority of pilots. It is good to see a manufacturer open a dialog with the soaring community about this.

There is, however, two issues I regard as important:

1) Most gliders often fly very close to stall speed, while thermalling. A too simple warning device would be activated often during flight, and thus do more harm than good (the “Cry Wolf” syndrome).

2) Most of these accidents occur in connection with not only high Angle of Attack, but also uncoordinated flying. There was an excellent article by George Thelen in the U.S. Soaring Magazine about this, describing the optical illusions that make us fly slow and uncoordinated while close to the ground.

So we need a device that can sample more than just speed and AoA, but also the degree of (un)coordination of the flight. And since the vast majority of these freak accidents occur close to the ground, some way of ground-proximity detection, to avoid the Cry Wolf thing. Maybe this could be as simple as activating the device only when gear is down. That would deal with most of the landing phase accidents, at least.

– Maybe in the future, the GPS could compare with the built-in altitude map of the World, and activate the system when within a certain distance from ground?

There must be many people with ideas out there, and the technology is certainly there. Therefore, I have taken the liberty to copy this posting to the other German manufacturers (from

http://www.glider-manufacturers.de)

– Let us use the Internet as the powerful tool it is..

Safe Soaring,

Lars Peder

The problem is that if you set the warning at a high enough speed to cover a mis-flown approach or final turn, it alarms all the time when thermalling.

So you set the warning speed down so that normal thermalling is not bugged by alarms, and this negates its use for the circuit….

I guess you could incorporate things such as undercarriage and full-flap switches, but many people only lower the gear and full flap after the (potentially hazardous) final turn ….

Our speed regime is rather unusual for aviation, where we spend a considerable time operating below normal approach speed.

Advanced avionics could no doubt solve it (using radio height for instance) but would possibly cost more than the glider.

Finally, people in emergency situations have been known to ignore warning noises, so even if a system could be made to work it is still no proof against disaster. “I landed gear up because the sound of the horn distracted me” …..

No substitute for proper training, common sense, airmanship, and a sense of increased natural caution when within, say 1000 ft of the ground.

Ian Strachan

I guess nothing can be idiot proofed (but, perhaps, idiot resistant).

Once I am in the vicinity of the airport I lower my gear and set the landing flaps. I check both when I turn down wind. I check them again when I turn base. And I do one last check when I turn final. Call me paranoid, but I’ve never landed gear up. Special diligence has to be applied if you are doing a skinny straight in approach (i.e. contest). I recommend keeping your left hand on the gear handle (if it is located on the left – some gliders have it on the right hand side) so it is constantly on your mind. I know one former contest pilot who made the field but forgot to lower his gear. And this was on very rough asphalt.

Tom

Hmmmmm

I used to do the same until I landed wheels up! After a very hot and long day under the canopy and perhaps a little dehydrated. Competition finish, pull up, roll into downwind leg, wheel down, flaps to 10 degrees, check water taps open, check air brakes. Turn base, size up the landing area, all clear wheel is down, radio call finals. 3rd set of check as I crossed the fence.

Wheel down? Ummmm Ahhh Ummm Ahhhh. Not sure, Move lever, sinking too far …. smell of hot gelcoat on ( luckily ) grass! B……S!!!!

Ian

The LS-9 is equipped with a stall warning. It is enabled only when the engine is extended, but for a glider it could be coupled to the extended gear…

Bye

Andreas

KARL,

I DON’T KNOW WHERE TO START TO HAVE A CRACK AT YOU . BUT I HAVE ALL YOUR COUNTRY’S CERTIFICATIONS TO FLY FIXED WING AIRCRAFT.

IF WE AS SAILPLANE PILOTS WANT OR NEED A STALL WARNING SYSTEM WE MAY AS WELL HANG OUR BALLS UP ON A RACK!

THE REASON THAT YOU ARE A SAILPLANE PILOT IS THAT YOU CAN FEEL THE AIR SPEED, WING LOADING, WAY IN WHICH THE AIRCRAFT FEELS IN YOUR HANDS.

IF YOU CAN’T FEEL THIS YOU MAY BE BETTER OFF FLYING CESSNA’S BECAUSE THEY HAVE STALL WARNINGS.

REGARDS

TRACEY

LOOK FORWARD TO YOUR COMMENT

My Comment? Too many good pilots are dead!

I think that this is enough as my comment!

About 10 years ago OSTIV held a sailplane stall warning design competition. It was won by a Polish entrant with a unit that sensed the differential pressure between the sailplane pitot and a small flush orifice located on the fuselage nose slightly below the pitot. I was not a judge, but I thought I could see problems with rain clogging the orifices, and also errors caused by side slipping.

The unit that I entered placed 2nd. It used a simple home made wing top surface airflow separation sensing vane connected to a $2 piezo electric horn mounted in the cockpit. It performed well, but it was deemed too fragile for club glider use. The unit is described in the 7/90 issue of Soaring Magazine.

I have used mine for many years on both my Ventus A and Nimbus 3 sailplanes, and I consider it to be a good safety device for me. Mine is mounted on the wing root fairing top surface. The stall sensor vane performs fairly well there, and I do not have to remove it when I remove the glider’s wing.

I set the unit to activate when I come within about 10% of the stalling airspeed. That not only gives me adequate stall warning during towing and flight maneuvers, but it assists me in optimizing my thermal climbs. With a laminar winged sailplane that keeps me within the low drag laminar bucket of the airfoil. At 77 years of age I need all the help I can get!

Dick Johnson

I agree with you! I fly my Cessna 172 on short field landings by listening to the pitch of the stall warning and watching the IAS closely. With 10 to 15 mph headwind component and 40 degrees of flap, I can land and stop comfortably in less distance than most of the glider club members can accomplish with the 2-33 and in less distance than a lot of the Cessna pilots need to touchdown.

That’s why I finally ordered the DSI with my DG-808B.

See you all week after next.

Jim Brewster

Comments after having published the complete article:

Hi

First off, let me give you my deepest condolence for the loss of your friend and a fellow pilot of all of us.

Secondly, let me tell you that, even though I can understand why you did so, I don’t think it makes any good to anybody, especially you, to keep that “What am I doing…” statement in your page. You are not manufacturing mines, guns or knifes.

You make wonderful, state-of-the-art machines that enable many form a motivated, solidary community of people that share something among all.

Unfortunately, risk is a part of the pilots community. It has always been that way, and all of us have chosen to live with it. We could have freely chosen the other way, and we can do so at any moment. It won’t hurt to remember that you, K.F., are doing so much for increasing the security in gliders, so blaming yourself for an unfortunate accident is out of the question.

What indeed is inside the question are some other thoughts you can read in the same page. A stall warning in high performance gliders, where stalls can happen much more suddenly than in calm school planes, could indeed save some accidents IMHO. A speed warning could probably be manufactured within the airspeed indicator box and probably at a reasonable cost. Finally, a gear warning could also save some more incidents; probably a proximity device similar to those used in some modern cars to aid parking could be used here.

Those are obviously no new ideas, I am just trying to let you know that here is another pilot (with limited experience though) that believes that are good ones.

Only one more thought: while I am fully supporting your ideas, and I am deeply convinced that technology is there to help and that sport aviation could benefit more from the technology than what it does now, I also feel that an inappropriate use of it can be almost as bad as no use at all. Example: The F-5 motor glider that I began flying this winter has a stall warning with light and sound. It triggers exactly in the critical moment of any landing. It was no good to learn about the presence of that device in my first landing in the type!

Technology can do better than that: you can use feed ground distance information to the stall warning indicator as well as to the gear up indicator.

As usual, you are granted permission to use my words, all or part of them, as you consider appropriate.

Keep up the good work!

Alfredo Sola

Administrador del sistema

Hello Karl,

I am a relatively new student. I obviously don’t have the experience and knowledge to comment on the advice given by many distinguished pilots that respond to your articles.

I would however like to share my thoughts as a new pilot, if I may.

First of all, my flight training regarding stall recognition and especially proper airspeed in landing patterns is emphasized before and after every flight which includes of course the importance of coordinated flight. It appears to me that the students and the instructors are the club members who are benefactors on a regular basis but some members seem to forget occasionally and mishaps occur.

The best way to learn and retain information is to teach.

Maybe if we were all in some form of a teaching role during our flying years we would all be less likely to forget.

Part of my job is to evaluate assembly and maintenance procedures within the industry that I work in. It has been my experience to find a wide variety of interpretations and skill levels among even a small sampling of customers. For this reason alone we try to fool-proof our product as much as possible and I totally agree with the use of a Stall Warning Device.

I’ve been told that performing a landing pattern becomes less stressful as experience is gained. I hope that my attitude never will get too complacent while performing in a landing pattern because I can see that things can happen quickly when a pilot relaxes and suddenly something goes wrong. I’ve already seen and heard about too many mishaps in the few short months that I’ve been receiving instruction.

I will not stop flying but I will treat this sport with the respect it deserves. We came close to loosing an experienced member and friend two weeks ago but he will be fine after landing short and crashing into a steel fence.

I am very sorry about the loss of your friend.

Respectfully,

Peter Eberhart

Finger Lakes Soaring Club

I’ve just read your latest newsletter, and the accident seems inexplicable.

But the primary cause , it seems to me, was the effort to complete the pattern from only 100m.

If there was a cockpit problem causing him to abort the launch, a better plan would have been to make a 180 degree turn and land back downwind. I don’t know what the weather conditions were, but depending on wind and field length available, that would have been the safest plan.

There’s no way to make a safe pattern from 100m, even in a Nimbus, unless the entry speed is very high.

I wonder if he had a medical problem. A heart attack, or onset of extreme pain (kidney stone, gall bladder attack, severe nausea).

The stall warning issue is secondary, but while on that subject; we have audio varios, so why not have airspeed audio? Silent above 60 Kt., a mellow tone from 59 – 40 Kt., then a “peep-peep-peep” below 40 kts. Of course the limits would need to be set for the particular glider being flown. I think Dick Johnson’s sensor could do this if set up properly. The only problem would be differentiating the two audio sounds in the cockpit. I switch my audio vario off when I enter the pattern anyway.

In this case, I wouldn’t have had it switched on in the first place.

I have to say, however, that the best way to stay out of trouble is to pay attention and have a good plan.

Nothing can beat those.

John Daniell

DG-300 Owner since 1984

Dear Mr. Weber,

First of all, I am terribly sorry about the lost of your friend Jens.

Maybe I can imagine a bit how do you feel: long time ago, I lost friends twice due to the stall accident.

The first in a glider, the second in a powered plane.

Specially the first accident could be avoided by a stall warning system (the student pilot thought that his glider turned into a steep dive, while actually his wing has dropped; his reaction was the opposite of what he had to do).

The second one was more the matter of “playing” with the aircraft, however it is the stall and the wing drop on 100 m that induced the tragedy where two people died.

Technically speaking, stall warnings are possible. Why are we missing them?

As you were saying, commercial reasons can be very strong. If only ONE manufacturer introduce this device as standard equipment, people will think that his wings are bad and so nobody will buy his planes.

However, Cessna and Piper and many other manufacturers of powered planes are building the stall warning as standard equipment. And they still sell their planes, all around the world.

Simply, because they ALL do it. There is no difference. So if DG, Schempp-Hirth, Schleicher, Schneider, Grob, Scheibe, Diamond etc. all together build the stall warning in their products, starting tomorrow, the problem is solved!!!!! It is easier to write this down than to make it happen, I know.

Further, glider pilots do not expect a sound or light warning. We were always told the signs of a coming stall are the lower noise (specially when flying with open window), low forces on the ailerons (due to the low airspeed) and finally the well known buffet of the tail. And because we think that Cessna and Piper are airplanes “for granny’s” and “chickens”, we don’t want stall warnings!

When flying in the thermal, we fly close to the critical angle of attack. A stall warning often activated in these circumstances will be qualified as “unreliable”. There is nothing so bad as an unreliable safety device!

Have you heard the story of an airline pilot crashing the B-727 into the hill with an unreliable ground proximity warning system?

Seconds before the impact, on the warning “Pull up”, the pilot sad “Shut up”! This could be heard on the cockpit voice recorder………….. 148 people died in that accident.

We could solve this by switching off the system immediately after the gear retraction (but we do not have retractable gears on all planes). And taking the number of “gear up” landings with gliders into account, it would be easy to come into the situation of a good safety device, which was switched off…………

“Gear up” landings are often made in situations of high stress, where we are also likely to fly imprecisely and stall.

So, we have a long way to go. But it is not all that bad. Glider pilots around the world largely accepted the safety cockpits, though these do not increase the performance, only the safety. Tests of parachute systems are in progress. The specific problem with the stall warning is that it has something to do with our piloting technique. And you can tell a glider pilot anything you want, but not that he can not fly…….

Best regards,

Alex Ivanovic

P.S.

feel free to publish this on your site, if you want.

I will look if we can use magazines like Piloot & Vliegtuig or Thermiek

to further promote this and other safety related items.

Response to Safety Article:

Hello Mr. Weber

I would like to send my condolence for the lost of your friend.

About safety I think that no matter how well trained, well organized and experienced one may be there will be that day when something escape one mind that will lead to a minor or major accident. No one is perfect, even the best pilot make mistake. Therefore I believe that security device are a very good thing.

My motto is, if it can happened it will. It is just a matter of time to see it happening. I support your ideas to promote stall warning devices, and other warnings devices. In my opinion these devices will get more popular with time.

I also think that this idea should be carried further by improving and extending these devices to other aircraft components.

Statistic’s are clear: 95% of aircraft accidents are due to pilot mistake, therefore we should take this into consideration and provide all the safety support needed to reduce these accidents. The technology is there and is getting affordable, we should take advantage of it. It is my opinion that we should benefit of a lot more electronic and efficient safety devices, your DSI is a very good step forward. Hopefully this is just the beginning of much more sophisticated and automated devices that the DG company will build later.

One way to stimulate theses safety devices is, maybe, to lobby insurance companies to make a rebate on the insurance for gliders. The more safety devices the more reduction one get. Just like alarm systems in houses.

Or to lobby government to do tax reduction on the buying of gliders with safety devices in order to compensate to some extent the price raised by these devices.

Réal Le Gouëff

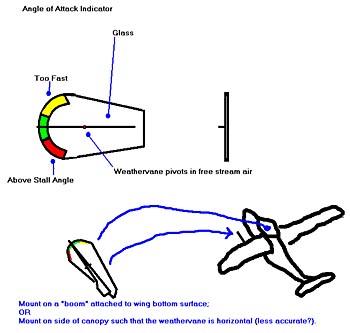

Angle of Attack indicator to prevent stalling

Enjoy your website. Especially liked your safety articles. Like you, I do not understand why gliders do not have a stall warning device. Here is something I use. Do you think you could modify this to work with your airplanes?

I ordered a Russia AC-5M. Once I get the plane, I am going to look at installing the AOA indicator on the AC-5M. The AC-5M comes with taped-on wing root fairings that I think could be modified to include a “boom” just like my power plane. Another idea is to mount the AOA indicator in the side vent window on the canopy….just have to make sure the device is subjected to free stream air flow.

If I can prove the airflow around the sides of the canopy mimics the free stream airflow, I can minimize drag even further. An ideal solution would be to add a second yaw string; but place the yaw string vertically on the side of the canopy so that it measures “up/down” instead of “left/right”. The inside of the canopy could then be painted with tick marks to show the stalling angle.

The advantage of this instrument to me is in order to use it, you HAVE to look outside the cockpit. Additionally, the simplicity leads to high reliability. Anyway, except for extreme competition where ALL drag is critical, I do not think this device would create a serious drag penalty.

John M. Jones

Stall warning

Karl:

You are absolutely correct that gliders need stall warning devices. Keep pushing!

By the way, this newsletter is the best thing to come to soaring in a long time. Keep up the hard work!

Dennis Olcott

Colorado, USA

Stall Recognition

Hello again Karl,

As a low time student I’ve been fortunate to fly in good lift conditions recently thus practicing low-speed thermalling techniques working on stall recognition and rudder wing recoveries from incipient spins. I have been able to greatly improve my stall awareness during these sessions and my reactions are becoming automatic as I’m sure they are to every competition or cross country pilot in this sport. I believe that the most important thing that I learned was that a glider can stall at any speed.

I’ve read about this but did not fully understand until I experienced the situation.

After numerous recoveries I began searching for another thermal. (I was flying a Schweitzer 2-33). Flying into very mild wind of 5 – 10 knots I adjusted my speed to 55 mph, which I thought was well above stall speed. I began to experience some mild shudder and increased my speed to 60 mph which still gave me an occasional shudder. Some confusion reigned until I realized that I was not flying coordinated and finally understood the importance. Keep that Yawstring straight!!

I realize that confusion or similar actions in a landing pattern could result in heavy consequences. ( I lost a total of 700 ft of altitude before adjusting).

After mentally reviewing such a scenario especially in a landing pattern on a busy, hot, stressful day I can see myself forgetting or overlooking one thing or another which is not acceptable to me and must be reinforced by either using a proper checklist well ahead of entering the landing pattern, Stall and Gear warning devices and anything else that can aid in proper decision making.

I also understand that most glider pilots are also professional power pilots and participate in this sport because it offer’s simplicity and serenity and would not like to “complicate” their cockpits with more bells and whistles. This is understandable and will have to be a personal choice until insurance companies demand it.

Unfortunately I already see a trend developing in the USA where-by insurance companies no longer want to provide “club insurance” and would prefer to insure the more lucrative individual instead. We are not helping the situation with an overall increase in accidents and incidences the last two years.

Please Fly Safely!

Peter Eberhart

Stall warning device

Dear K-F.

I have read your articles with interest. One thing that comes to my mind is that many (most?) gliders have a limit for the elevator movement to reduce the possible AoA somewhat. The Olympia Meise was an early glider incorporating such a limit to reduce the risk of stall/spin accidents.

A further development could be to have a somewhat flexible stop, perhaps a gas spring, that is activated at a slightly lower AoA than stall, so the pilot can feel some added resistance when he is pulling more than sensibly. Some device that causes the stick to vibrate when reaching this limit (a kind of “stick shaker) could provide further warning, very useful because most gliders provide very little stall warning. Perhaps the stick shaker could be disabled when the brakes, landing gear and engine are retracted and the altitude is much higher than needed for recovery.

I think a device that works along these lines would be easier to accept by all pilots than something with acoustic or optical warning, although such warnings would be acceptable when the glider is in landing configuration.

I think experienced pilots would not accept sound or light warnings coming on several times each turn while thermalling. for this case the ideal would be a device that helps keeping the drag low, like the one Dick Johnson describes.

After all, getting maximum performance out of the glider is what every glider pilot strives for.

It is interesting to note that many pilots seem not to know when the glider is stalled. One pilot in my club spun several turns by mistake in a Standard Cirrus. He

obviously held the stick fully back all the time, because the spin direction reversed several times when he applied opposite rudder. The glider somehow recovered, probably just because he let the stick go. My experience is that most gliders recover immediately when the back pressure is released somewhat. So it is just a question of giving a clear indication to the pilot about what is going on, and a stick shaker is the obvious solution. It is not for free, but I think it would save lives.

Ake Pettersson

June Newsletter – Sad Accident & Safety Discussion

Dear Mr. Weber,

I was very sorry to hear of the loss of your friend. I hope that you and everyone else who was affected can start to feel better soon, and can remember all the good times without being too sad.

I am a relatively new glider pilot (working at the Silver ‘C’) but I have always been surprised at the lack of safety features in gliders – especially when compared to other forms of transport such as the car.

So I completely support your wish to introduce as many additional safety precautions into glider as possible. As you say, most of the safety options already exist in other forms of transport, or are already proven.

One problem in making this happen soon is the age of most aircraft, with so many old machines, especially the club aircraft (I fly at Deeside beside Aboyne in

Scotland). But the sooner new aircraft adopt new features, the sooner they will appear in the second-hand market…

Please keep up the good work and remember that a great many glider pilots are very grateful for all your hard work and dedication.

All the best,

Brian Rogers

Aberdeen, Scotland.

http://www.miskin.demon.co.uk

Two Years later:

Another good friend

The discussions about stall warnings have died down recently – and you can take that quite literally.

Nothing has happened regarding this issue in the past two years.

Nothing, apart from the message I received just before Christmas 2001.

Another friend of mine had died, in a gliding accident in the African desert.

One of the other pilots from the group who flew there told me what had happened:

On the last day of his life the pilot flew his own glider as usual, a two-seater self launcher with over 25 m wingspan. He was not a very tall pilot, and as he was flying on his own we can probably assume that he flew with a rearward C of G position.

He had taken the first launch of the group as he had set himself quite a big task. However the thermals hadn’t properly kicked off yet. So he slowly lost the height he had after switching off the engine, and found himself at a low height above a saltpan near the airfield from where he had started. This saltpan was the only landing option in the area as the rest of the desert is completely unlandable.

From the logger that was recovered from the glider one could see that he tried to gain some height in very weak lift. He had probably by now seen the other pilots, who had started later, soaring far above him to distant turning points while he just didn’t reach sufficient height to connect with the thermals. Who wouldn’t get nervous in this situation?

He finally gave up on his attempts to gain height and started the engine when his height was down to 130 m (just over 400 ft) (!!!). The engine started ok, but did not crank properly and didn’t produce any power. This wasn’t necessarily an engine fault – experience shows that pilots tend to make mistakes when they have to start the engine manually in a rush at low height. Anyway, he desperately tried to get the engine running and lost sight of the saltpan.

Having lost even more height he now had to do a 180° turn to reach his field.

The consequence: stall, spin, vertical impact, no chance of survival.

The other pilots couldn’t believe their eyes when they reached the wreck. They recovered the data from the logger and all came to the same conclusion: “a typical beginner’s error”.

The pilot had been flying gliders for 30 years. Gliding was “his life”.

Who would believe such a story – until one experience it?

Let me add a different and unfortunately totally fictitious ending to this horrific and yet so typical tragedy:

Imagine what the pilot might have told the other pilots about the flight in the evening over a nice slice of ostrich steak:

“……. and then I had to use the fan after all, but the effin’ thing wouldn’t work properly. I tried everything with the effect that in the end I had lost sight of the saltpan. So I throw the glider into a turn and pull the stick back – and this really annoying stall warning buzzer goes off. This is really all I need now!

So I put the nose down, turn even more tightly so that the wingtips almost meet at the top, and there it is again in front of me: the saltpan.

On finals I see what the problem was – the choke was fully open even though the engine was still warm. After I’ve shut the choke the engine suddenly has the necessary oomph, I speed across the saltpan at about 5 m height, and pull up at the end of it until I reach the thermals.

Well, in the future I will certainly start the engine at a safer height.”

Unfortunately this ending is just wishful thinking – my friend is dead.

What I am trying to say, though, is aimed at YOU:

He and the other pilots wouldn’t even have noticed that a buzzer for a small sum of money would have saved his life on that morning. – He probably would even have found the buzzer really annoying!

In this connection the only thing I can think of is the Marlene Dietrich (or rather Pete Seeger) song which ends in:

When will they ever learn? When will they ever learn……..?

Translation: Claudia Buengen

Betreff: Stall Warning

Datum: Thu, 25 Apr 2002 14:11:29 EDT

Von: SUGARFOX

Karl,

Thanks for a very honest and well written discussion of the attributes of a stall warning system. Although I do not fly a DG, I admire your candor and the information you publish in your newsletters. I too, believe that gliders should have such a system. I believe that even the most experienced pilots can be momentarily distracted from monitoring their speed. When this distraction happens at the wrong time, the results can be very tragic.

Stan Nelson

Here is my five cents worth on this debate:

Definitely, a stall warning shall become a standard equipment on gliders. Arguments, that glider pilot shall feel the airplane in his ands and feel it, is just wishful thinking. The reality is, that even highly experienced pilots, who definitely had a good feeling of their planes, stalled, crashed and died. sadly, it has happened in front of my eyes too.

To make things worse, there are many glider pilots, who do not fly a lot, or fly irregularly, simply under pressure of modern life and they cannot devote as much time to gliding as they want (don`t we all do?) It is the fact of life.

Therefore, a stall warning system shall emerge in gliders. It will not help, if that system is not of a good design. Annoying buzzer, beeping all the time will do no good. It is in human nature that unreliable safety devices will be ignored – even highly trained and experienced crews in passenger jets did it, with disastrous consequences.

I am surprised to see suggestions that airspeed should be used as a signal to trigger the alarm. Stalling has only to do with one thing:

critical angle of attack (AOA), which is peculiar for every airframe/airfoil. Let`s not forget that angle of attack is not the only variable. Also aerodynamic shape of the glider can change – configuration changes (flaps setting, airbrakes…) changes in airfoil (bugs, and in particular, raindrops or even ice). Flying uncoordinated, does not affect critical angle of attack, but it affects airflow and lift and drag distribution – so measuring AOA with one sensor might not be enough to take into consideration that kind of disturbance. Also, aileron movement changes shape of the wing/airfoil considerably.

As an instructor, I like to demonstrate in our club acro twin seater Fox, how a glider can spin into direction, opposite of the aileron input, thus showing how banking away from a ridge at high AOA (either low speed or higher speed and increased G load due to turn) can actually cause a wing drop towards a ridge. Many pilots were surprised and needed explanation what has happened. And it will not help if a perfect sensor is designed, if the warning is present to the pilot in a confusing manner. Another buzzer in the cockpit is, by my opinion, not the best solution. There are GPS pings (reaching turnpoint), landing gear buzzers, maybe even mobile phone beeps (Batt. low, SMS received…) and a confusion in critical moment is easy. Visual signals/messages are no good, as we do not look much on instrument panel, especially not when turning low level towards landing spot with a heart pounding somewhere in the neck – when most stall/spin accidents happen.

Big jets went thru this issue some 25 years ago – and solution was synthetic voice (“Natasha”) saying all sorts of (frightening) things like: FIRE left engine, Terrain, terrain, PULL UP, PULL UP, STALL, STALL…..) Finally, there is a power supply issue: if there is another electronic gadget installed, it will take another slice from electrical supply.

Years ago, in our club gliders we had a radio station and simple electrical variometer. Today, there are complex variometer/ GPS equipped computers, palmtop computers with big colour displays, maybe even transponders and FLARMs – but battery is still the same. Even a small solar panel on top of instrument panel cannot help with all this thirsty electronic gadgets. It has happened to me twice, that everything went quiet just when I entered a looong and low final glide towards airport and glidepath information from GPS computer was essential-but not available.

Not all Cessnas and Pipers have a vane, protruding from leading edge that moves a switch to activate stall warning horn. Some have just a hole/slot in the leading edge, connected via tube to a simple blowhorn at the wingroot (near pilot`s head.) When AOA increases, at certain moment airflow thru this system reverses, and horn sounds. First quietly, and then more and more loud, as AOA and flow of air thru the tubing increases. This is the best and simplest safety device I have ever seen in aviation.

Maybe there is a possibility to carefully determine which combination of holes in the wingroot (to avoid troubles with wing removal) could provide a reliable and strong enough airflow to “power” a simple horn or whistle in the cockpit. Other way might be thru electronic sensors (AOA sensor, vane in leading edge or sensor(s) for lift separation, taking into account configuration changes and providing sithetic voice alarm. Passenger jets employ a system, where AOA sensor (rotating vane, which you can normally see somewhere below cockpit windows) and switches, sensing position of flaps, slats, landing gear… provide signals to stall warning computer, which, based on preset values of AOA for different configurations, sounds alarm and also stick shaker. (and even stick pusher – not to speak about fly by wire jets, where all this is incorporated in basic flight control system computers) It is interesting to see, that this system blindly gives alarm at preset values, without knowing actual shape of the wing and consequentlly airflow separation – that can be influenced by ice accumulations considerably, so take off with iced wings is still a problem, as stall might occour earlier, with lower AOA than normal.

That`s my five cents worth contribution to this debate.

Karl, hope to see you soon here in Lesce!

Regards,

Miha Avbelj

Hello,

I appreciated the article on stall warning in your recent newsletter. I also agree with you that we need to improve safety. A stall warning indicator would be an important contribution for new pilots and those that only fly occasionally. It probably does need to be couple to the landing gear/flaps because the warning given during thermally would be too late during final approach to landing. The warning needs to be given at a higher speed. I also believe an angle of attach indicator might be of more benefit than the too late stall warning.

I believe a bigger problem is loss of situational awareness. Good pilots crash and we wonder why. They would not have crashed if they knew what was going on. Something distracted them or they just were unable to process as much information as usual and they missed something important. Saturday here in North Carolina was very hot and every student I flew with deteriorated in performance. Usually I see an improvement in performance and when the improvement stops we end the lesson. But Saturday every student started out fairly good and deteriorated. One of them was a competition pilot needing a Flight Review, one was preparing for a flight test, one had recently soloed and one was a new pilot needing a rear seat checkout. I attribute this to dehydration.

A friend of mine was a very good pilot and had flown for years. He started having trouble landing his ASW-24. So I asked him to do a checkride. 2 or 3 times. He would come out on a cool day, climb into the L13 Blanik and give me a perfect flight. But he came out one hot day, assembled his ASW-24, helped launch a couple of gliders, and went out for a short flight and crashed on landing. He tells me it was not his fault because when he felt the glider sink he closed the spoilers. Two of us on the ground watched him turn final low with the spoilers appearing to be full open. The glide path did not look like he would reach the runway. We watched the attitude of the glider go more and more nose up. But the spoilers remained full open. Just before he reached the runway, he ran out of speed, dropped onto a sign, and destroyed the glider. Fortunately he was unhurt. But to this day he maintains that he closed the spoilers when the glider started to settle and does not agree with us that he was in trouble when he turned final. When we tried to check him out in our new Grob, we started seeing spells of 10 to 20 seconds where no one appears to be flying the glider. (bank angle increases, nose drops, etc.) I think he is loosing awareness for short periods of time. He still drives and talking to him he seems perfectly normal. But still, we cant let him fly.

A couple of years ago an older member turned a club glider off the runway and into a ditch. He had been out to see the runway with another club member in a golf cart, so he knew what was beside the runway. Why did he turn? He wasnt stupid. He lost situational awareness. Afterward I heard that he had appeared confused after flights recently and before this flight.

I really believe the problem we must address is loss of situational awareness, although I am not a doctor and have no training in the issue. Im sure your friend who had been flying 40 years didnt suddenly forget how to fly. He lost situational awareness for some reason. A stall warning indicator might have caused him to focus on airspeed, but he was low before then and probably had no place to go. The problem started long before that.

Tough problem.

My condolences for your loss. I also would like to see us stop the accidents.

Best regards,

Roger Fowler

President, North Carolina Soaring Association